On a very high level, web applications tend to have two major parts: state and user interface (UI). An application starts with an initial state and presents that state to the user through UI. The user takes some action through a UI element that modifies the initial state. The new state is then presented back to the user for more actions. The figure below shows the interaction between a state and UI in a hypothetical application that allows logged in users to create blog posts.

At any given point in time, an application needs to store different types of information in memory. For example, it needs to know whether or not a user is logged in or how many blogs a user has posted. State is like a repository for storing all of this information. This state is then made available to various data structures in the application. Functions in the application perform different operations on it, resulting into a new state.

In the Pure Functions section, we defined a state as something that represents all the information stored at a given point in time that a function has access to. Conceptually, an application state works the same way. It just contains a lot more information than a function-level state.

Model

In Elm, we represent the state of an application with something called a model. A model is just a data structure that contains important information about the application. Imagine a simple app for incrementing and decrementing a counter. The only thing we need to track in this app is the current value of a counter. Here is what the model definition for this app looks like:

type alias Model

= IntIt’s just an Int. A model doesn’t necessarily have to be complicated. It all depends on how complex the app is and how many different things it needs to track. For a simple counter app, all we need is a number that tells us what the current value is. A model is generally defined as a type alias.

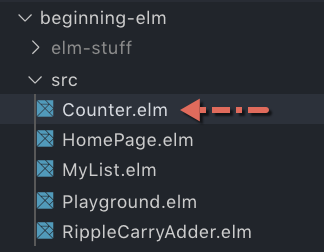

Let’s add the above model definition to a file and start building a counter app in Elm. Create a new file called Counter.elm in the beginning-elm/src directory and add the code below to it.

module Counter exposing (Model)

type alias Model =

IntThe definition above doesn’t create a model. All it tells Elm is what our model looks like. Here is the code that actually creates our initial model:

initialModel : Model

initialModel =

0Add the code above to the bottom of Counter.elm.

View

Next, we need to present our initial model to the user. Add the following code to the bottom of Counter.elm.

view : Model -> Html msg

view model =

div []

[ button [] [ text "-" ]

, text (String.fromInt model)

, button [] [ text "+" ]

]The view function takes a model and returns HTML code. Behind the scenes, the div function in Elm produces the <div> element in HTML, and the button function produces the <button> element. The text function doesn’t represent any HTML tag. It just displays a plain text by escaping special characters so that the text appears exactly as we specify in our code.

The first argument to div and button represent a list of attributes. The second argument represents a list of nested elements. The Elm code in the view function is equivalent to the following HTML code.

<div>

<button> + </button>

String representation of our model

<button> - </button>

</div>The div, button, and text functions are all defined in the Html module included in the elm/html package. The Html module provides full access to HTML elements through normal Elm functions. Let’s import it in Counter.elm.

module Counter exposing (Model)

import Html exposing (..)

.

.Since we can treat HTML elements as plain old Elm functions, we can apply all the nice things Elm has to offer to the view code as well. For example, we can refactor the duplicate code out into separate functions and reuse them from different places in our app. We can write automated tests for the view code using the same tools used for testing any other Elm code. Elm compiler will even let us know if we made any mistake in the view code.

The view function isn’t responsible for rendering HTML on a screen. All it does is take a model and return a chunk of HTML. It’s a pure function that returns the same HTML code given the same model. To actually render HTML on a screen, Elm uses a different package called elm/virtual-dom behind the scenes. Don’t worry about how this package works now. We’ll explore it in detail in the Virtual DOM section later in this chapter.

The elm/html package depends on elm/virtual-dom. That’s why it was

automatically installed and listed as an indirect dependency in the elm.json file when we ran elm make in the Building a Simple Page with Elm section.

{

"dependencies": {

"direct": {

"elm/html": "1.0.0",

},

"indirect": {

"elm/virtual-dom": "1.0.2"

}

}

}We don’t need to import any of the modules included in the elm/virtual-dom package in our code because we shouldn’t be using it directly. It only exists to support the modules defined in the elm/html package.

The view function’s type annotation suggests it returns a value of type Html msg which means the HTML code generated by view is capable of producing messages of type msg. We’ll find out what msg is in the Update section below.

view : Model -> Html msgApplication Entry Point

Add the following code to the bottom of Counter.elm.

main : Html msg

main =

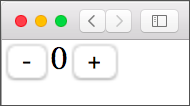

view initialModelAs usual, main acts as an entry point for our app. All it does is pass the initial model to the view function. Run elm reactor from the beginning-elm directory in terminal if it’s not running already and go to this URL: http://localhost:8000/src/Counter.elm. You should see something like this in the top left corner of your browser:

Update

Our app is utterly uninteresting at the moment. The buttons don’t do anything. That’s because we haven’t specified what should happen when the buttons are clicked. Let’s do that next. The first thing to do is define messages that represent the actions users can take. Add the following type definition right above main in Counter.elm.

type Msg

= Increment

| DecrementMsg is a custom type with two constants. When the + button is clicked, our app will receive the message called Increment and clicking the - button will generate the Decrement message.

- Message

- The term “message” doesn’t have any special meaning in Elm. It’s not a special type or a data structure. We could have very well called it “action” or “event” or “do this thing”. The official documentation and the Elm community prefer “message”, so we’ll go with that.

Unlike Model, we didn’t define Msg as a type alias because there is no built-in type in Elm for representing messages. In contrast, our Model is just an int value. So we made it a type alias that simply redefines the existing Int type.

Handling Messages

To handle messages, we need to define a new function. Add the following code above main in Counter.elm.

update : Msg -> Model -> Model

update msg model =

case msg of

Increment ->

model + 1

Decrement ->

model - 1The update function increments or decrements the model based on which message the app receives.

Generating Messages

We’ve created a mechanism for handling messages, but we still don’t have a way to create them. Let’s take care of that. Modify the view function to fire messages when the + and - buttons are clicked.

view : Model -> Html Msg

view model =

div []

[ button [ onClick Decrement ] [ text "-" ]

, text (String.fromInt model)

, button [ onClick Increment ] [ text "+" ]

]Previously, the HTML returned by view wasn’t creating any messages, so we just used msg as a placeholder in its type annotation.

view : Model -> Html msg

view model =

...Now, view uses the onClick function from the Html.Events module to generate messages of type Msg. Let’s import Html.Events in Counter.elm.

module Counter exposing (Model)

import Html.Events exposing (..)

.

.Msg is a concrete type, whereas msg is just a type variable. A concrete type always starts with an uppercase letter. A type variable, on the other hand, starts with a lowercase letter. Unlike the special type variable number we saw in the Type System section, msg doesn’t have any special meaning in Elm. We could have used any random name to represent a generic message in the previous version like this:

view : Model -> Html someMessage

view model =

...By replacing msg with Msg, we’ve made the view function much more restrictive. Now, it can only generate two messages: Increment and Decrement. Before, it could generate any message.

Wiring Everything Up

Here is how our main looks right now:

main : Html msg

main =

view initialModelPassing initialModel to view was enough when we were just displaying a static view. To allow interactivity, we need to add update in the mix. Modify main like this:

main : Program () Model Msg

main =

Browser.sandbox

{ init = initialModel

, view = view

, update = update

}And import the Browser module in Counter.elm.

module Counter exposing (main)

import Browser

.

.Note: The Browser module is included in the elm/browser package which was installed automatically when we ran elm make after our project was initialized in the Building a Simple Page with Elm section.

Elm Architecture essentially boils down to these three parts: model, view, and update. The entire application can be viewed as one giant machine that runs in perpetuity. The Browser.sandbox function describes the structure of that machine: take an initial model, present it to the user, listen to messages, update the model based on those messages, and present the updated model back to the user again.

The diagram below illustrates the interaction between the Elm runtime and various components in our app.

Refresh the page at http://localhost:8000/src/Counter.elm and you should be able to increment and decrement the counter.

main Function’s Type Annotation

Not sure if you noticed, but the main function’s type annotation changed from Html msg to Program () Model Msg when we introduced the Browser.sandbox function. Like any other function in Elm, main takes the type of whatever expression it happens to return. We already know what Html msg means. Program () Model Msg means an Elm program that has a model of type Model and accepts messages of type Msg. The unit type () indicates no values are passed to our app when it’s initialized. In chapter 8, we’ll see an example that shows how to pass values to an Elm program during initialization.

Model as a Domain Concept

You may wonder why do we even need to define Model. We could simply replace Model with Int in initialModel and update’s type annotations like this:

initialModel : Int

initialModel =

0

update : Msg -> Int -> Int

update msg model =

...And everything should work just fine. That is a valid point. However, by defining Model, we’ve given a name to the value that flows through our app. This makes our code easier to read. In a simple app, the benefits of naming things properly aren’t huge, but in a large app, a well named domain concept such as Model can add tremendous value from maintenance standpoint.

Summary

In this section, we learned the basic components of the Elm Architecture: model, view, and update. In the next section, we’ll find out what virtual DOM really is and what benefits we get from it. Here is the entire code for the counter app:

module Counter exposing (main)

import Browser

import Html exposing (..)

import Html.Events exposing (..)

type alias Model =

Int

initialModel : Model

initialModel =

0

view : Model -> Html Msg

view model =

div []

[ button [ onClick Decrement ] [ text "-" ]

, text (String.fromInt model)

, button [ onClick Increment ] [ text "+" ]

]

type Msg

= Increment

| Decrement

update : Msg -> Model -> Model

update msg model =

case msg of

Increment ->

model + 1

Decrement ->

model - 1

main : Program () Model Msg

main =

Browser.sandbox

{ init = initialModel

, view = view

, update = update

}