The good old space race is back on. Wouldn’t it be great if we could help out some of these incredibly ambitious companies by letting them reuse our code to find out whether or not their spaceship can leave the Earth too? We can do that by creating a function that encapsulates our logic. Before we do that, let’s understand what a function is in mathematics first.

Note: You may be wondering why I keep taking you back to the wonderful world of mathematics every time I try to explain a concept in Elm. That’s because Elm is a functional programming language which gives it a strong mathematical foundation. Elm implements concepts from mathematics without distorting them. So by understanding how they work in mathematics first, it’s easier to understand them later in Elm. As a bonus, you know where these concepts originally came from. This doesn’t mean you need to have a strong math background to learn Elm. Everything you need to know is covered in this book.

A function, in mathematics, is a relationship from a set of inputs to a set of possible outputs where each input is mapped to exactly one output. Functions in Elm also work the same way.

Let’s write a function in Elm called escapeEarth that takes a value from an input set of velocities and maps it to a value from an output set of instructions.

> escapeEarth myVelocity = \

| if myVelocity > 11.186 then \

| "Godspeed" \

| else \

| "Come back"

<function>We can now call this function with different velocities to find out whether or not a spaceship can leave the Earth.

> escapeEarth 11.2

"Godspeed"

> escapeEarth 11

"Come back"Like if expression, we can assign the value returned by a function to a constant.

> whatToDo = escapeEarth 11.2

"Godspeed"

> whatToDo

"Godspeed"Function Syntax

Functions are so critical to Elm applications that Elm provides an incredibly straightforward syntax for creating them. No ceremony is required, such as using a special keyword or curly braces which is common in many languages.

Function Application

Once we create a function, we need to apply it to a value to get a desired output. In mathematics, function application is the act of applying a function to a value from the input set to obtain a corresponding value from the output set. You have already seen an example of a function application above: escapeEarth 11. When a function is applied, its name should be separated from its argument with whitespace. If a function takes multiple arguments, they too should be separated from each other with whitespace.

Note: In most programming languages, it’s more common to say “calling a function” instead of “applying a function”. Those two phrases are interchangeable in meaning.

- Parameter vs Argument

- The terms parameter and argument are often used interchangeably although they are not the same. There is no harm in doing so, but just to clear things up, an argument is used to supply a value when applying the function (e.g.

escapeEarth 11) whereas a parameter is used to hold onto that value in function definition (e.g.escapeEarth myVelocity).

Earlier we learned that all Elm applications are built by stitching together expressions. How do functions fit into this organizational structure? Functions are values too like numbers and strings. Since all values are expressions, that makes functions expressions as well. Because of this, functions can be returned as a result of a computation. They can be passed around like any other value. For example, we can give them to another function as an argument. Functions that take other functions as arguments or return a function are called Higher Order Functions. We will see many examples of higher order functions soon.

Functions with Multiple Parameters

The escapeEarth function above takes only one argument: velocity. But, we can give it as many arguments as we want. Let’s add one more parameter to its definition so that it can tell us whether or not our horizontal speed is fast enough to stay in an orbit.

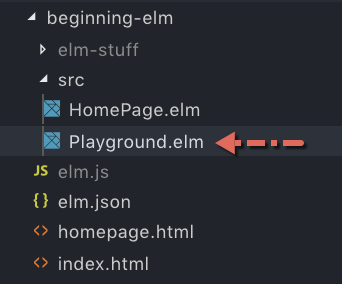

The next code we will write is a bit difficult to type in the repl without making any mistakes, so we will write it in a file instead. Create a new file called Playground.elm inside the src directory which is located in the root directory (beginning-elm) of the Elm project we created in the last chapter. We will use the Playground.elm file to experiment with various concepts in Elm. Here is how the directory structure should look like so far.

- Filename

- Elm style conventions dictate that filenames are also written in Camel Case. Unlike constants, the first letter in a filename should be written in uppercase though. The first letter of each subsequent concatenated word should be capitalized. Elm doesn’t throw an error if we don’t follow this convention, but there is no reason not to follow it.

Put the following code in Playground.elm.

module Playground exposing (main)

import Html

escapeEarth myVelocity mySpeed =

if myVelocity > 11.186 then

"Godspeed"

else if mySpeed == 7.67 then

"Stay in orbit"

else

"Come back"

main =

Html.text (escapeEarth 11.2 7.2)The first two lines define a new module called Playground and import the Html package. Don’t worry about module and import yet; we’ll cover them later. Next is our function escapeEarth. We give it one more parameter called mySpeed. If myVelocity is not greater than 11.186, it will use the else if branch to compare whether mySpeed is equal to 7.67. If yes, it returns "Stay in orbit". Otherwise, it falls to the else branch.

The last function is main. The execution of all Elm applications start with this function. It’s a regular function like any other. It just happens to be the entry-point for an application. We apply a function called Html.text to the result produced by yet another function application: escapeEarth 11.2 7.2. Html.text takes a string and displays it on a browser. It’s important to surround escapeEarth and its arguments with parentheses. Otherwise, Elm will think we are passing three arguments to Html.text which takes only one argument. This is because Elm uses whitespace to separate a function name from its arguments. We can chain as many function applications as we want.

Go to the beginning-elm directory in your terminal and run elm reactor. After that open this URL in a browser: http://localhost:8000. You should see src as one of the directories listed in the File Navigation section. Click on it. Now you should see the Playground.elm file. If you click that file too, elm reactor will compile the code in it and display the string “Godspeed”.

Partial Function Application

When we applied the escapeEarth function above, we pulled the value for speed out of thin air. What if it’s actually computed by another function? Add the following function definitions right above main in Playground.elm.

computeSpeed distance time =

distance / time

computeTime startTime endTime =

endTime - startTimecomputeSpeed takes two parameters: distance covered by a spaceship and travel time. Time in turn is computed by another function called computeTime. Here’s how the main function looks when we delegate the calculation of speed to our newly created functions:

main =

Html.text (escapeEarth 11 (computeSpeed 7.67 (computeTime 2 3)))Yikes! Chaining multiple function applications looks hideous and hard to read. But what if we write it this way instead:

main =

computeTime 2 3

|> computeSpeed 7.67

|> escapeEarth 11

|> Html.textAh, much better! To compile the new code, refresh the page at http://localhost:8000/src/Playground.elm. You should see the string “Stay in orbit.”

The nicely formatted code above is possible because Elm allows partial application of functions. Let’s play with some examples in elm repl to understand what partial functions are. Create a function called multiply with two parameters in the repl.

> multiply a b = a * b

<function>When we apply it to two arguments, we get the expected result.

> multiply 3 4

12Let’s see what happens if we pass only the first argument.

> multiply 3

<function>Hmm… It returns a function instead of giving us an error. Let’s capture that function in a constant.

> multiplyByThree = multiply 3

<function>Now, let’s see what happens if we apply this intermediate function to the second (and final) argument.

> multiplyByThree 4

12

> multiplyByThree 5

15multiplyByThree is a partial function. When Elm sees that we haven’t given enough arguments to a function, it doesn’t complain. It simply applies the function to given arguments and returns a new function that can be applied to the remaining arguments at a later point in time. This has many practical benefits. You will see plenty of examples of partial function application throughout the book.

Forward Function Application

Let’s get back to that fancy |> operator that made our code look so pretty. It’s called the forward function application operator. Since that name is too long, the Elm community refers to it as the pipe operator. It is very useful for avoiding parentheses. It pipes the result from previous expression to the next one.

The pipe operator takes the result from the previous expression and passes it as the last argument to the next function application. For example, the first expression in the chain above (computeTime 2 3) generates number 1 as the result which gets passed to the computeSpeed function as the last argument.

Backward Function Application

There is another operator that works similarly to |>, but in backward order. It’s called the backward function application operator and is represented by this symbol: <|. Let’s deviate from our spaceship saga for a bit and create some trivial functions to try out the <| operator. Add the following function definitions right above main in Playground.elm.

add a b =

a + b

multiply c d =

c * d

divide e f =

e / fadd, multiply, and divide are functions that do exactly what their names suggest. Let’s create an expression that uses these functions. Modify the main function to this:

main =

Html.text (String.fromFloat (add 5 (multiply 10 (divide 30 10))))Ugh. Even more parentheses. Refresh the page at http://localhost:8000/src/Playground.elm and you should see 35.

Note: The add function returns a number, but Html.text expects a string. That’s why we need to use the String.fromFloat function to convert a number into a string. We’ll cover the String module in detail later in this chapter.

Let’s use our knowledge of the |> operator to turn the expression in main into a beautiful chain.

main =

divide 30 10

|> multiply 10

|> add 5

|> String.fromFloat

|> Html.textLet’s see how the above expression looks when we rewrite it using the <| operator.

main =

Html.text <| String.fromFloat <| add 5 <| multiply 10 <| divide 30 10Not bad, huh? Both |> and <| operators can be used to avoid parentheses, but |> is better suited for writing pipelined code. That’s why it’s called the “pipe” operator. Elm provides other higher-order helper operators like these. You can learn more about them here.

Operators are Functions Too

In Elm, all computations happen through the use of functions. As it so happens, all operators in Elm are also functions. They differ from normal functions in three ways:

Naming

Operators cannot have letters or numbers in their names whereas the normal functions can. Similarly, functions cannot have special characters in their names whereas the operators can.

Number of Arguments

Operators accept exactly two arguments. In contrast, there is no limit to how many arguments a normal function can take.

Application Style

Operators are applied by writing the first argument, followed by the operator, followed by the second argument. This style of application is called infix-style.

> 2 + 5

7Normal functions are applied by writing the function name, followed by its arguments. This style of application is called prefix-style.

> add a b = a + b

<function>

> add 2 5

7We can also apply operators in prefix-style if we so choose to.

> (+) 2 5

7The operators must be surrounded by parentheses. We can’t apply normal functions in infix-style, but we can create something that resembles infix-style by using |>.

> 2 |> add 5

7- Custom Operators

- Elm doesn’t allow us to define custom operators. It’s quite difficult to come up with a good operator that uses simple symbols to visually illustrate the meaning of an operation it represents. Therefore, a code base with many custom operators is generally hard to read. It’s better to use named functions instead.

-

Elm used to support custom operators prior to version

0.19. If you are interested in further exploration, this document explains the reason behind removing them in great detail.